JavaRCA: Java Recipe for Carefree dependency Administration

Modularization and Dependency Management in Java projects does not have to be a mess.

Take a fresh and playful perspective at this topic with the concepts and tools available in and for

modern Java.

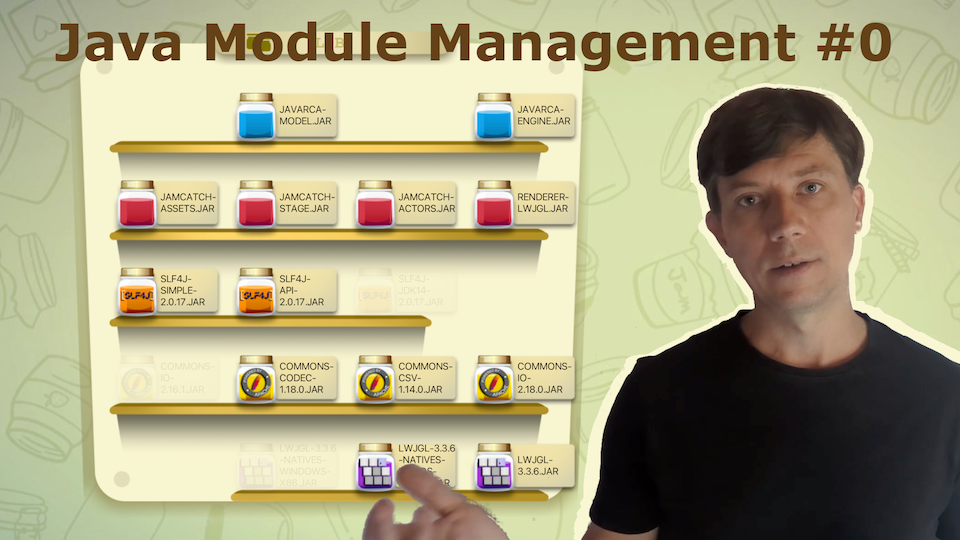

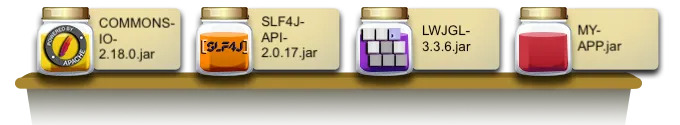

Your Java program is made up of JAR files — the modular building blocks of your software.

Most come from open-source libraries, which are easy to add: like jars full of delicious jam, free for

the taking from public repositories.

But over time, these sweet-looking dependencies carry a hidden cost. As libraries evolve, maintenance

becomes a burden. In long-lived projects, dependency management often turns into a tangled mess —

tedious, error-prone, and time-consuming.

With a modern Java toolset, you can avoid that. The JavaRCA recipe provides a clear guideline to help

you do just that.

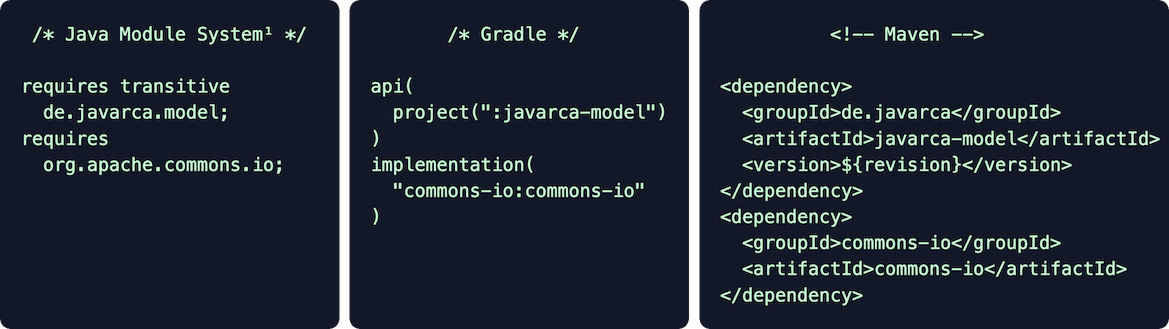

Get Started: Clarify your choice of Dependency Definition notation

The JavaRCA recipe works with the common approaches to define dependencies in Java projects.

For new projects, it's recommended to use the Java Module System for dependency definition, with Gradle as the build tool.

If you rely on frameworks that don't yet support the Module System well, you may use Gradle plainly.

If you prefer Maven – or if you work on an existing Maven-based project – you can use that too, with or without the Module System.

What matters most is being intentional and aware of your setup.

/* Java Module System¹ */ requires transitive de.javarca.model; requires org.apache.commons.io;

/* Gradle */

api(

project(":javarca-model")

)

implementation(

"commons-io:commons-io"

)

<!-- Maven -->

<dependency>

<groupId>de.javarca</groupId>

<artifactId>javarca-model</artifactId>

<version>${revision}</version>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>commons-io</groupId>

<artifactId>commons-io</artifactId>

</dependency>

¹If you use the Java Module System for dependency definition, you still need Gradle or Maven as build

tool.

You use a GradleX plugin to bridge the Module System with one of the build tools.

You use a GradleX plugin to bridge the Module System with one of the build tools.

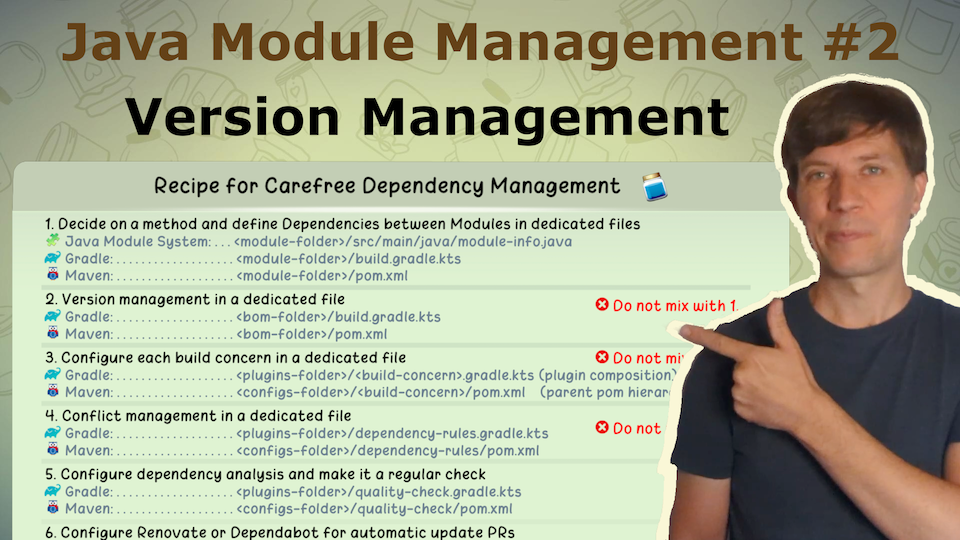

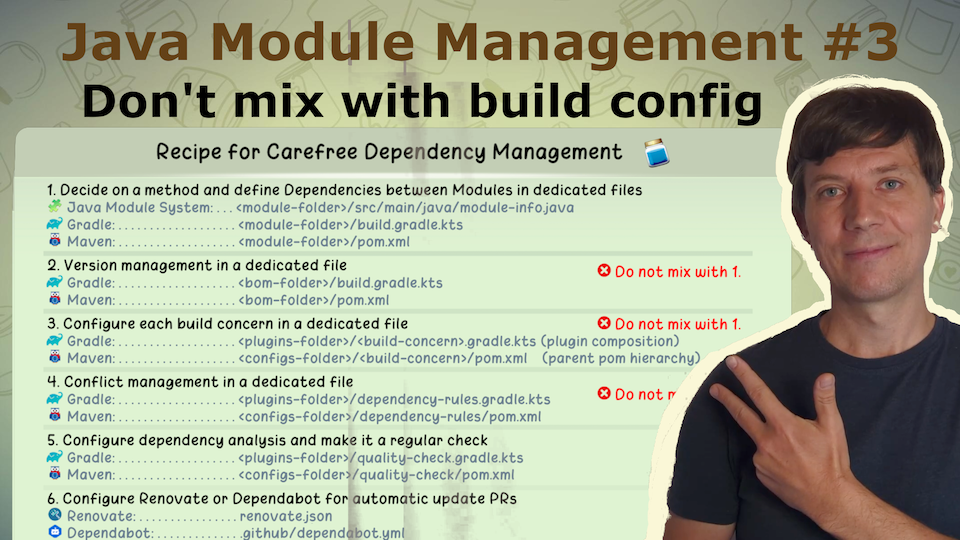

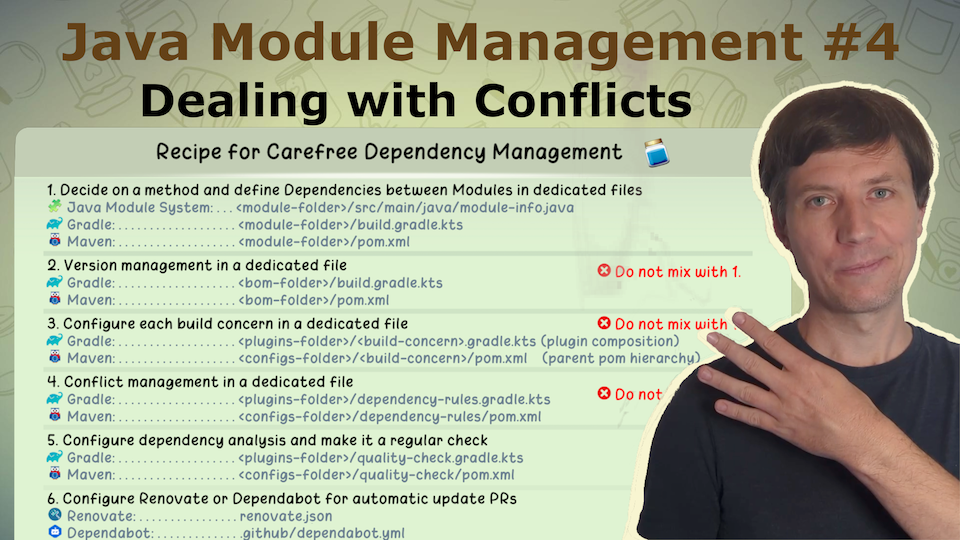

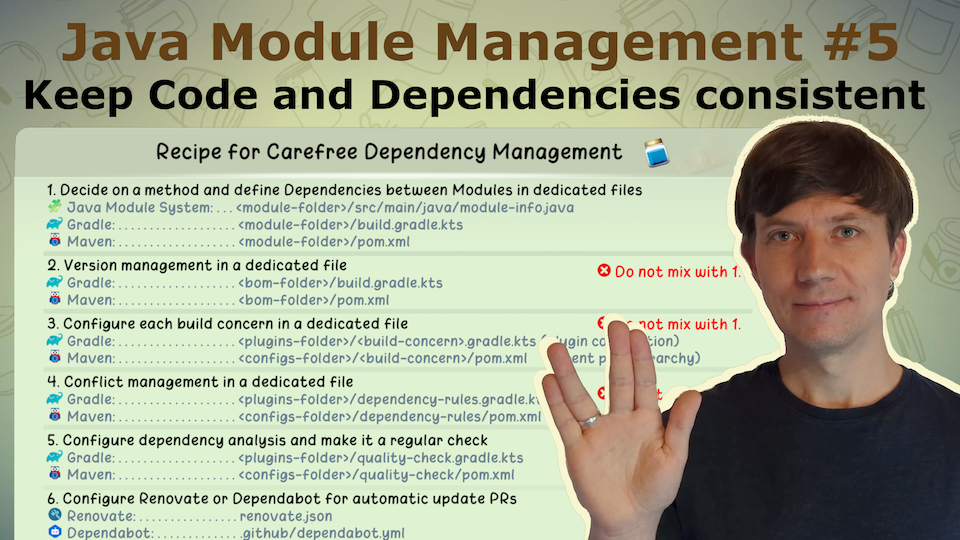

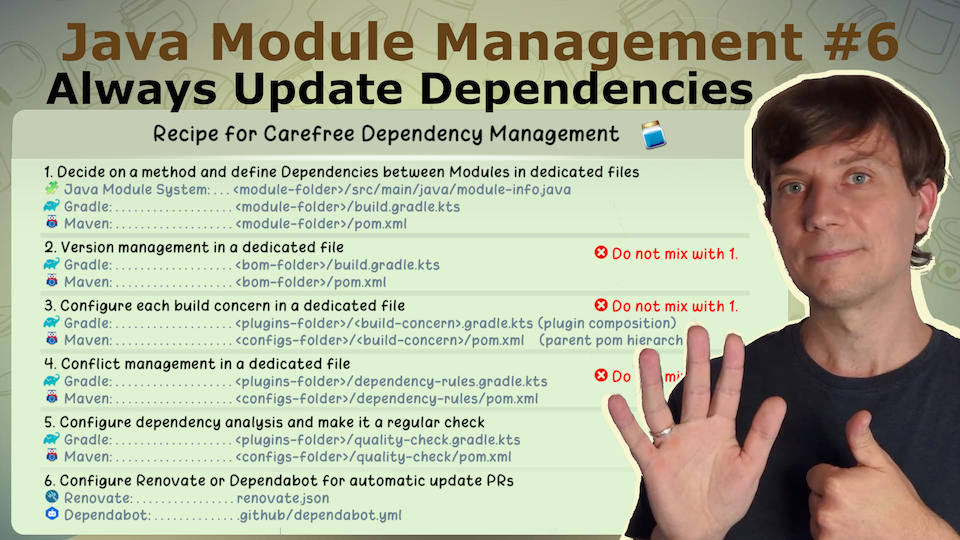

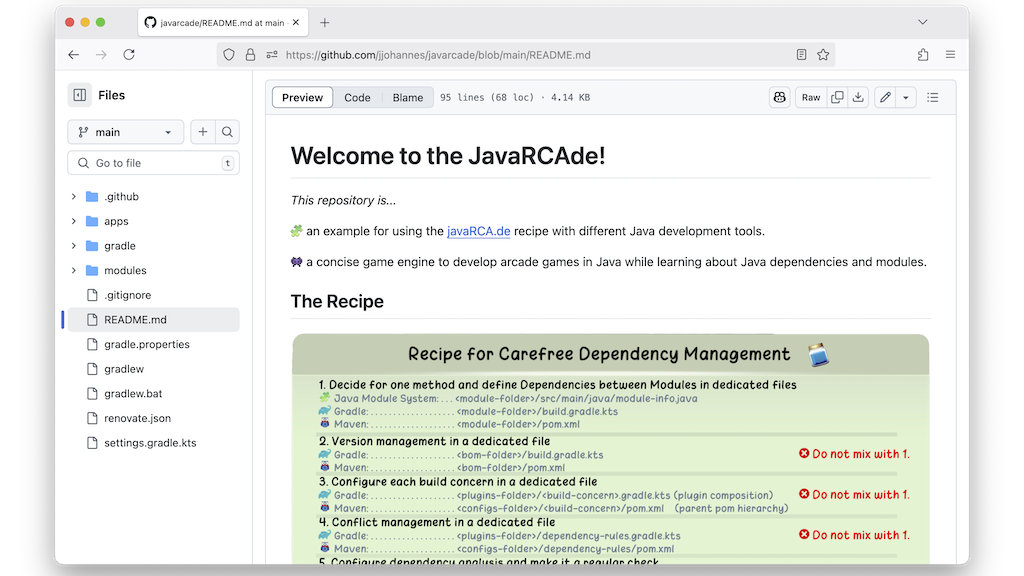

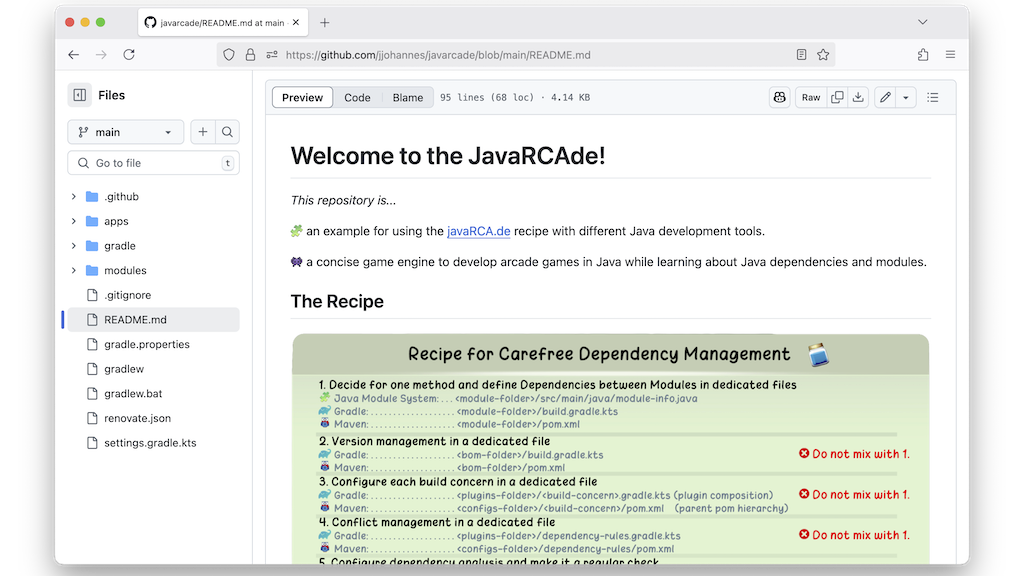

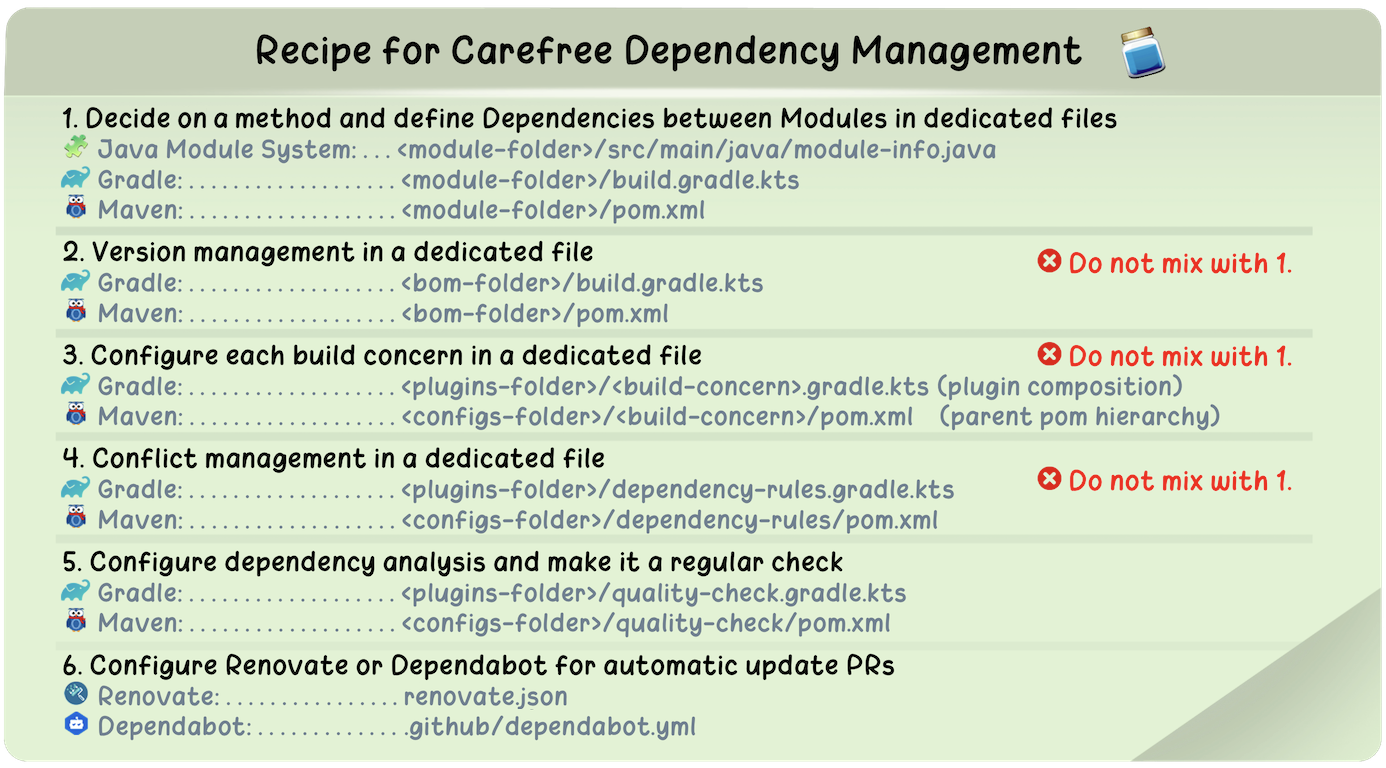

The Recipe

Recipe for Carefree Dependency Management

- Decide on a method and define Dependencies between Modules in dedicated files

Java Module System: . . <module-folder>/src/main/java/module-info.java

Java Module System: . . <module-folder>/src/main/java/module-info.java Gradle: . . . . . . . . <module-folder>/build.gradle.kts

Gradle: . . . . . . . . <module-folder>/build.gradle.kts Maven: . . . . . . . . <module-folder>/pom.xml

Maven: . . . . . . . . <module-folder>/pom.xml - Version management in a dedicated file

Gradle: . . . . . . . . <bom-folder>/build.gradle.kts

Gradle: . . . . . . . . <bom-folder>/build.gradle.kts Do not mix with 1.

Do not mix with 1. Maven: . . . . . . . . <bom-folder>/pom.xml

Maven: . . . . . . . . <bom-folder>/pom.xml - Configure each build concern in a dedicated file

Gradle: . . . . . . . . <plugins-folder>/<build-concern>.gradle.kts

Gradle: . . . . . . . . <plugins-folder>/<build-concern>.gradle.kts Do not mix with 1.

Do not mix with 1. Maven: . . . . . . . . <configs-folder>/<build-concern>/pom.xml

Maven: . . . . . . . . <configs-folder>/<build-concern>/pom.xml - Conflict management in a dedicated file

Gradle: . . . . . . . . <plugins-folder>/dependency-rules.gradle.kts

Gradle: . . . . . . . . <plugins-folder>/dependency-rules.gradle.kts Do not mix with 1.

Do not mix with 1. Maven: . . . . . . . . <configs-folder>/dependency-rules/pom.xml

Maven: . . . . . . . . <configs-folder>/dependency-rules/pom.xml - Configure dependency analysis and make it a regular check

Gradle: . . . . . . . . <plugins-folder>/quality-check.gradle.kts

Gradle: . . . . . . . . <plugins-folder>/quality-check.gradle.kts Maven: . . . . . . . . <configs-folder>/quality-check/pom.xml

Maven: . . . . . . . . <configs-folder>/quality-check/pom.xml - Configure Renovate or Dependabot for automatic update PRs

Renovate: . . . . . . . renovate.json

Renovate: . . . . . . . renovate.json Dependabot: . . . . . . .github/dependabot.yml

Dependabot: . . . . . . .github/dependabot.yml

The Recipe in Detail

Item 1: Conscious choice of method for defining dependencies

If we want to use an open source module, we have to define that somewhere. The relationships between the modules of our own software also have to be specified somewhere. There are several options for this in the Java ecosystem. Therefore, the first step is to make a conscious decision: How and where do we define dependencies?

Not making a clear decision leads to inconsistencies and with that unnecessary complexity. The definition of dependencies reflects parts of the software architecture in the code. It is important to keep an eye on these and to adjust them consciously if necessary. All developers should know how and where dependencies are defined. And they should feel just as responsible for these definitions as they do for the code itself. Dependencies are usually defined in other formats than Java (e.g., Kotlin DSL or XML) that can lead to a mental disconnect. There is a risk that the dependency definitions are only seen as part of the build configuration and not as part of the software itself.

To counteract this, it is important to make a conscious decision: In which files are dependencies defined, and in which notation? One historical aspect regularly leads to misunderstandings: The most commonly used tools – Gradle and Maven – are primarily known as build tools. However, they are both build tools and dependency management tools. (In the past, Ant and Ivy were based on the idea of providing build tools and dependency management tools separately.) This distinction is particularly important from the perspective of code ownership: while build configuration can be maintained by individual Gradle or Maven experts, dependency management is part of the software and should be owned by all developers. This requires understanding the definitions, which becomes difficult when build configuration and dependency definition are mixed in the same notation and the same files. That is why a clear separation of aspects into multiple files is the basic theme of this recipe.

The following approaches are suitable for separating dependency definitions from build configuration:

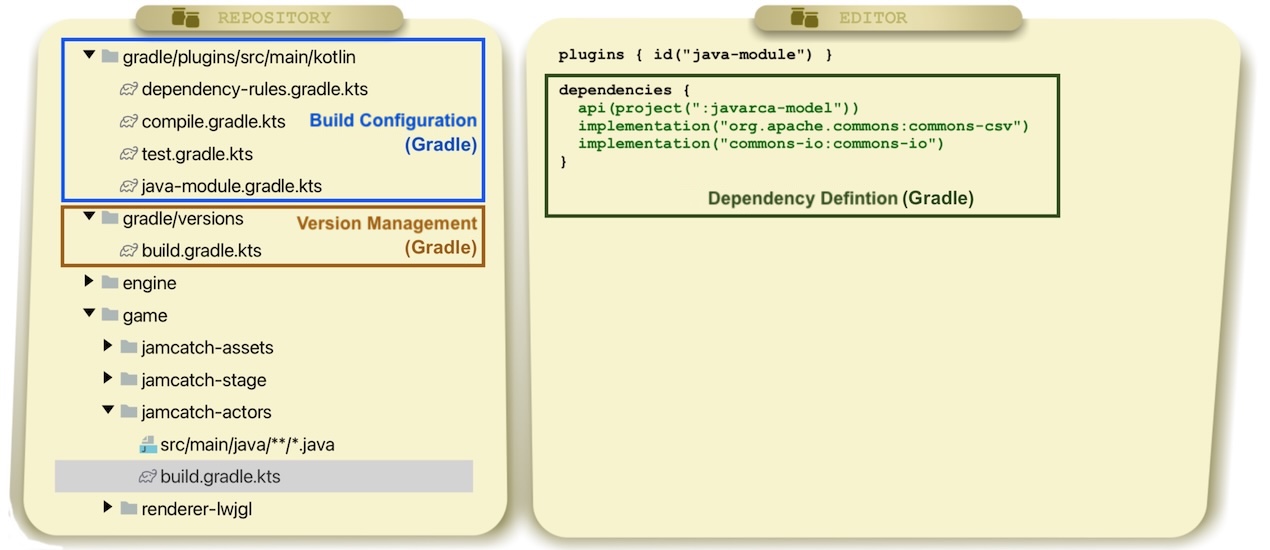

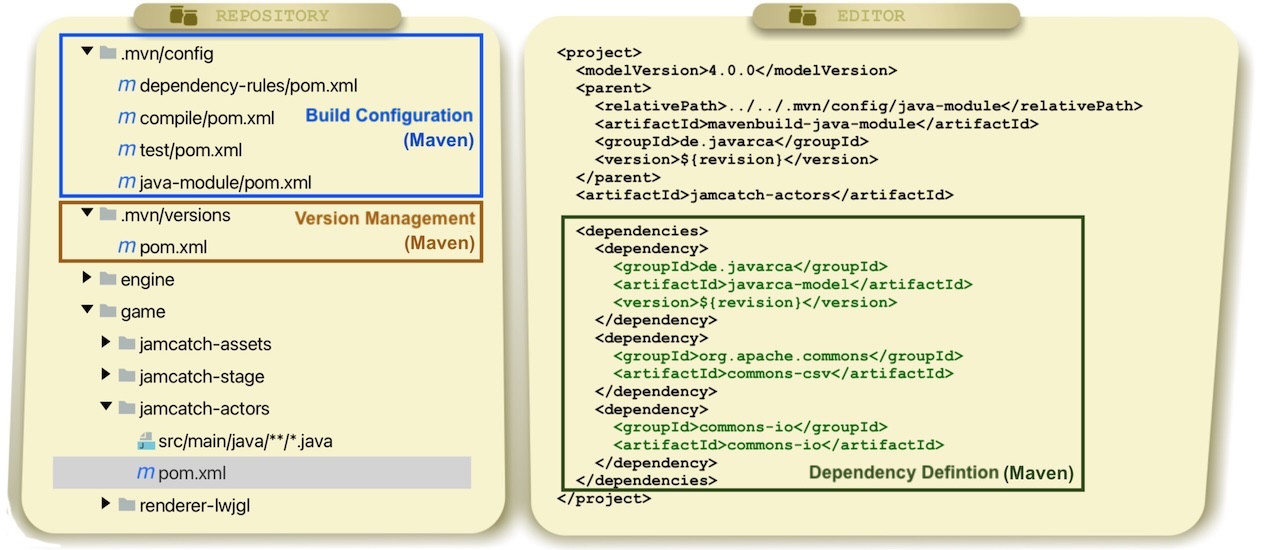

- A Gradle or Maven project usually has one tool-specific file per module: module/build.gradle (Figure 1) or module/pom.xml (Figure 2). Technically, both tools allow all aspects of dependency management and build configuration to be defined there (and in many projects this is exploited). The solution is to treat these files purely as dependency definitions. The files then clearly show the dependencies of the corresponding module. Developers can internalize the notation for dependencies – dependencies { ... } (Figure 1) or <dependencies>...</dependencies> (Figure 2) – without having to be Gradle or Maven experts.

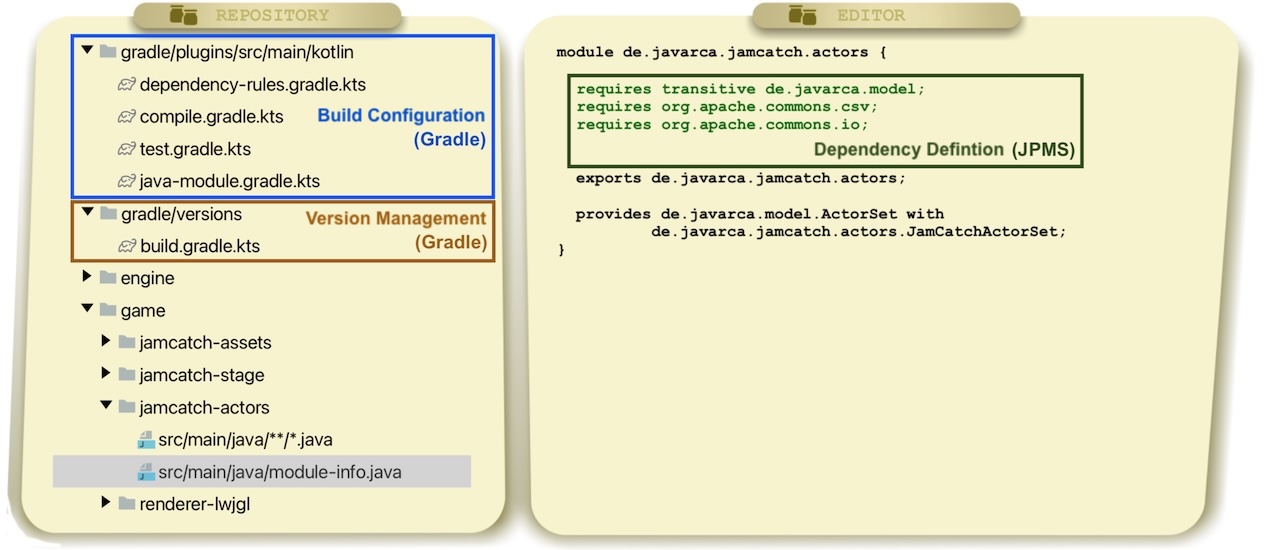

- Java offers its own notation for dependencies as part of the Java Module System (JPMS) with module-info.java files. This allows dependencies to be defined directly in Java (Figure 4) and thus independently of the build tool. If you use a plugin that forwards the information from module-info.java files to the build tool, this information does not need to be repeated redundantly in the tool-specific files (build.gradle or pom.xml). These non-Java files can then be almost empty or even omitted entirely. Developers take care of the code and dependencies of a module directly in Java and have little contact with tool-specific notation in their daily work (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Project that uses Gradle for dependency definition and Gradle as build tool

Figure 2: Project that uses Maven for dependency definition and Gradle as build tool

Figure 3: Project with module-info.java files for dependency definition and Gradle as build tool

Item 2: Version management in a dedicated location

Many of the defined dependencies (Item 1) point to open source modules. These modules are available in several versions and variants. A dependency management tool ensures that a JAR file is selected, downloaded, and cached for each module.

To perform this task, the tool (Gradle or Maven) needs information. The minimum information required is one version per directly defined dependency. Even if technically possible, this should not be specified directly together with the dependencies. A dependency such as Commons IO (Figures 1, 2, 3) can appear multiple times if it is required in several modules of your own software. However, the version used should be identical everywhere and therefore maintained centrally.

Centralized version management has long been considered best practice. This point of the recipe is therefore primarily about implementing this consistently: That is, not mixing versions with dependency definitions (Item 1).

Specifically, you can use the Bill-of-Material (BOM) concept introduced by Maven (Listing 2). Versions are defined in a separate file in a block specifically designated for this purpose – dependencyManagement. Gradle offers the same concept under the name Java-Platform and provides the dependencies.constraints block (Listing 1).

dependencies {

api(platform("org.slf4j:slf4j-bom:2.0.17"))

}

dependencies.constraints {

api("commons-io:commons-io:2.16.1")

api("org.apache.commons:commons-csv:1.14.0")

}

Listing 1: Gradle platform for centralized version management – gradle/versions/build.gradle.kts in Figures 1 and 3

<dependencyManagement>

<dependencies>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.slf4j</groupId>

<artifactId>slf4j-bom</artifactId>

<version>2.0.17</version>

<type>pom</type>

<scope>import</scope>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>commons-io</groupId>

<artifactId>commons-io</artifactId>

<version>2.16.1</version>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.apache.commons</groupId>

<artifactId>commons-csv</artifactId>

<version>1.14.0</version>

</dependency>

</dependencies>

</dependencyManagement>

Listing 2: Maven BOM for centralized version management – .mvn/versions/pom.xml in Figures 1 and 3

Item 3: Configuration of each software build aspect in a dedicated location

As described in Item 1, the dependency definition should be considered separately from the rest of the build configuration. A good prerequisite for this is to organize the build configuration as a whole in such a way that each aspect is configured in a clearly defined location.

Many projects lack a clear separation of individual aspects of the build configuration. This is probably because the tools do not specify any requirements for this and everything can be configured in a single file in no particular order. This leads to unnecessary complexity due to configuration files that are difficult to read and contain several hundred or even thousands of lines.

As with code, the solution seems obvious: we avoid unnecessary complexity by putting independent configurations into separate, sensibly named, and sorted files. This applies both to issues that affect the actual building of the software (e.g. setting Java compiler flags or selecting a test framework) and to things that require individual configuration in the context of dependency management (see Items 4 and 5).

This is where Gradle shines with its composition approach: each configuration file is technically a plugin, also called convention plugin, and these can be freely combined. This allows individual aspects to be defined in files such as compile.gradle and test.gradle and then composed into a java-module.gradle, which in turn is used in all modules (Figures 2 and 4). Maven makes this separation more difficult in current versions. Separation into multiple files is only possible via inheritance using parent POMs, where each file can only have one parent. Although this problem can be circumvented with a hierarchy of POM files (Figure 3), flexibility remains limited. In Maven 4.1, POM mixins introduce a new concept that addresses this issue. Mixins enable flexible composition of configuration aspects from separate files.

Item 4: Conflict management in a dedicated location

The most important feature of a dependency management tool, apart from downloading and caching artifacts, is selecting versions and variants and, if necessary, recognizing and resolving conflicts. In this regard, every tool is only as good as the data it receives. This data is obtained from the metadata accompanying the JARs (.pom and .module files).

However, this data is sometimes insufficient, and you need to provide additional information for your project – that is, the context in which you are combining existing modules in a new way.

There are a variety of conflicts that can arise when using and combining open source modules. Table 1 shows typical cases. If these are not resolved, or not even recognized, this usually leads to erroneous behavior.

There are cases where a conflict cannot be resolved fully automatically, because there is no clear right choice (for example, the choice of a logger implementation). In other cases, information is missing from the metadata to even recognize a conflict in the first place.

Similar to versions (Point 2), you want to identify and resolve conflicts in a consistent manner. The additional configuration required for this should therefore also be stored centrally in a file that applies to all modules of your software. This is important to avoid inconsistencies during testing. For example, it is undesirable if the unit tests of an isolated module use different versions than those that will later run in production.

Gradle and Maven offer different solutions in this area. Gradle generally has the more comprehensive feature set here and is therefore often the better choice for projects with high dependency management requirements. Regardless of the solution chosen, the configuration should be centralized as much as possible. The most suitable concept in Gradle is component metadata rules. This allows missing metadata to be added and incorrect data to be corrected (Listing 3). Since Gradle, with its variant-aware dependency management, offers a very expressive metadata format, it can also be used to control the selection of JARs according to operating system or other attributes. There is no equivalent in Maven. Therefore, you have to work with dependency exclusions to remove dependencies and replace them with others if necessary. With this method, it is more challenging to cleanly isolate conflict management. You can take this relatively far by defining exclusions in a dependencyManagement block in a parent POM instead of directly in dependency blocks (Listing 4). Maven does not support more extensive variant selection within a single build. However, different variants can be selected in separate executions via build profiles.

| Module | Feature we use | Possible conflicts |

|---|---|---|

| Commons IO | Reading files | --- |

| Commons CSV | Parses CSV files | Has dependency to Commons IO and there may be conflict with the Commons IO version we define |

| SLF4J | Logging | One of many logger implementations needs to be selected: slf4j-simple (logs directly), slf4j-jdk14 (logs via java.util.logging) |

| LWJGL | Graphics rendering | Provides multiple JARs for multiple operating systems; selection needs to be performed based on targer platfrom |

Table 1: Examples of version and variant conflicts in open source modules

jvmDependencyConflicts {

conflictResolution {

select("org.gradlex:slf4j-impl", "org.slf4j:slf4j-simple")

}

patch {

module("org.lwjgl:lwjgl") {

addTargetPlatformVariant("natives", "natives-linux", LINUX, X86_64)

addTargetPlatformVariant("natives", "natives-macos", MACOS, X86_64)

addTargetPlatformVariant("natives", "natives-windows", WINDOWS, X86_64)

}

}

}

Listing 3: Centralised patching of metadaten in Gradle – dependency-rules.gradle.kts in Figures 1 and 3

<dependencyManagement>

<dependencies>

<dependency>

<groupId>de.javarca</groupId>

<artifactId>javarca-engine</artifactId>

<exclusions>

<exclusion>

<groupId>org.slf4j</groupId>

<artifactId>slf4j-jdk14</artifactId>

</exclusion>

</exclusions>

</dependency>

</dependencies>

</dependencyManagement>

Listing 4: Centralised exclusions in a parent POM in Maven – dependency-rules/pom.xml in Figure 2

Item 5: Dependency analysis as part of the build process

If you follow Items 1 to 4, you will get to a clean setup. But as with everything in software development, this is only a snapshot. The software continues to evolve, and with it, dependencies between modules must also be constantly reevaluated. Without tool support, it is difficult to keep an overview.

When we work on the code of a module of our software to develop features or fix problems, we don't always think about the dependencies on other modules. Over time, this can lead to inconsistencies. Perhaps you have defined dependencies that are no longer used in the code. Or you accidentally use elements from dependencies that you have not defined, but which are still visible to the compiler.

There are tools that can help here by comparing the code with the declared dependencies and identifying unused dependencies, for example. Integrating such a tool into your build process ensures that inconsistencies do not arise accidentally and become problematic over time.

Specifically, there is the dependency analysis plugin for Gradle, which offers such analyses and integrates smoothly into Gradle build processes. In Maven, the Maven dependency plugin directly provides the dependency:analyze goal, which performs some of these checks.

Item 6: Automated version updates

As soon as we use an open source module, maintenance costs arise that are not entirely under our control. Whenever a new version is released, we should at least check whether an update makes sense in our project.

At first glance, this does not seem necessary: if a module works in my software, why should I update it regularly? Looking at a single module in isolation, the main reason is probably security. Time and again, security vulnerabilities are discovered in open source components and made public. Fixes for such vulnerabilities should be applied as quickly as possible to prevent your own software from becoming vulnerable. But of course, updates can also bring improvements, for example in performance, to your own software. Another reason why you should update all module versions regularly is the relationship between open source modules: In the Java ecosystem today, there is a wide range of modules that build on each other. This means that when one module is updated, versions of other modules often have to be upgraded as well to remain compatible with each other – see Commons CSV and Commons IO as examples (Table 1). If you only perform updates when it seems "absolutely necessary", you may find yourself in situations where you suddenly have to update "everything at once".

When it comes to tool support, this item differs from the previous ones: we have to take action even if we are not developing our own code. A good tool setup should be part of our code hosting platform and/or CI pipeline and should work even when no changes have been made to our code. Instead, it should inform us when an update for an open source module is available and automate the actual update as much as possible.

In recent years, several tools werde developed that can be used in addition to the dependency management tools in your code hosting platform and/or CI pipeline. The most common are Renovate and Dependabot. Both notify you when an update is available and automatically generate pull/merge requests to perform the update. Depending on which manual test steps are required, you can configure the degree of automation. It is important that if manual steps are necessary, they are integrated into the development process: for example, by reviewing all open requests on a weekly basis to ensure that updates are actually performed. If you use a platform such as GitHub, both tools can be easily set up via the associated app – often at no additional cost. The open-source core of Renovate can also be self-hosted and controlled via any CI system. If you do not want to or cannot use these tools, you can also use Gradle or Maven in your CI pipeline to inform about new versions and set up your own tooling on that basis.

Video Series

Users

Explore

Dive deeper into Java modularity and Gradle

Presentations

Support

Java and the Java logo are trademarks of the Oracle Corporation.

Gradle and the Gradle logo are trademarks of Gradle Inc.

Apache Maven and the Apache Maven logo are trademarks of the Apache Software Foundation.

Dependabot and the Dependabot logo are trademarks of GitHub Inc.

Renovate and the Renovate logo are trademarks of White Source Ltd.

Site operated by onepiece.Software.